Why would I write a YA novel where a girl falls in love with another girl? Did I set out on purpose to limit myself to a teeny-weeny little audience? And even among those few, brave readers, did I still want to get reviews that questioned why the main character had to be a lesbian? What was I thinking?

It’s simple, really. I had to write the story I wanted to read. The kind of story I needed when I was a teenager. I grew up in the 80s and 90s in a rural area, and I relied on the public library for all my reading. As you can imagine, I barely ever encountered another girl-loving girl in a book.

We’ve come a long way, baby — today’s teens have the internet, and some of them have gay-straight alliances at school, and the national dialog is expanding to address gender identity and the fluid nature of sexuality in a much more positive light — but being queer can still be dangerous. The New York Times reported in August that gay, lesbian and bisexual teenagers were at far greater risk for depression, bullying and many types of violence than their heterosexual peers. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that these adolescents were three times more likely than straight students to have been sexually assaulted. They skipped school far more often because they did not feel safe. At least a third had been bullied on school property, and they were twice as likely as heterosexual students to have been threatened or injured with a weapon at school. In the year leading up to the study, 29 percent of students who did not identify as straight had attempted suicide.

Even if it weren’t so vitally important, representation would still matter to me as a reader. Cis-het people see themselves reflected in books and movies and TV an overwhelming majority of the time, as do white people. Anyone else has to filter their experience in order to relate. I can appreciate the stuff of romantic love when it’s presented in girl-boy or (much less common) boy-boy pairings, but I identify as a lesbian, and it’s entirely different to see yourself as the star of the story.

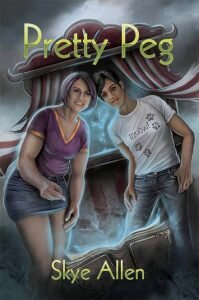

In my book Pretty Peg, the main character, Josy, is a plus-size teen who is enduring a whole range of family dysfunction. She’s kind of a smartass. She falls in love with an extremely cute girl and for most of the book she can’t quite believe this hottie actually likes her. Their romance is bumpy. Josy confronts her self-esteem issues and grows up a little more during the story. She spends just as much time solving a family mystery as she does thinking about kissyface. And oh yeah, she also gets the girl.

When I say I wanted to write about the kind of queer characters I wanted to read about, I don’t mean girls who sometimes kiss other girls for the benefit of a boy, or lesbian/bi girls who serve as diversity sidekicks for the main, straight character. Those girls have a place on the page and the screen, but they’re not enough for me. To have your own experiences be central, not in the margins. To read about three-dimensional characters who are real girls with real imperfections and real who-am-I questions. That’s representation.

Kate Brauning writes wonderfully about that on GayYA.org: “Love is hard, and awkward and messy and confusing and imperfect. And I want to see these books be those things, too. I want to read about girls who get it really wrong sometimes, and have it be okay and be part of falling in love. Their flaws and quirks and selves can be brought to the story without pieces of themselves being held back. If queer girls have to be closer to perfect than cis-het girls and aren’t allowed to mess up, get it wrong, and start over, then that’s another kind of tragedy because we’re being shown a world where perfection is demanded, we aren’t allowed to be human, and growth can’t happen.”

Kate Brauning writes wonderfully about that on GayYA.org: “Love is hard, and awkward and messy and confusing and imperfect. And I want to see these books be those things, too. I want to read about girls who get it really wrong sometimes, and have it be okay and be part of falling in love. Their flaws and quirks and selves can be brought to the story without pieces of themselves being held back. If queer girls have to be closer to perfect than cis-het girls and aren’t allowed to mess up, get it wrong, and start over, then that’s another kind of tragedy because we’re being shown a world where perfection is demanded, we aren’t allowed to be human, and growth can’t happen.”

YA is all about growth, but it’s also about mirroring actual human experience. Most good stories are. I say it’s time to expand the genre, to follow the lead of those intrepid readers who have been seeking out positive queer love stories all along. Bring on the real girls.